Secular Jewish culture embraces several related phenomena; above all, it is the culture of secular communities of Jewish people, but it can also include the cultural contributions of individuals who identify as secular Jews, or even those of religious Jews working in cultural areas not generally considered to be connected to religion.

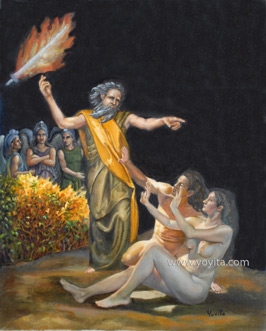

The word secular in secular Jewish culture, therefore, refers not to the type of Jew but rather to the type of culture. For example, religiously observant Orthodox Jews who write literature and music or produce films with non-religious themes are participating in secular Jewish culture, even if they are not secular themselves. However, Judaism guides its adherents in both practice and belief, and has been called not only a religion, but also a "way of life," and an identity, which makes it difficult to draw a clear distinction between Judaism and Jewish culture. Furthermore, not all individuals or all cultural phenomena can be easily classified as either "secular" or "religious". In some places where there have been relatively high concentrations of Jews, distinct secular Jewish subcultures have arisen. For example, ethnic Jews formed an enormous proportion of the literary and artistic life of Vienna, Austria at the end of the 19th century, or of New York City 50 years later (and Los Angeles in the mid-late 20th century), and for the most part these were not particularly religious people. In general, however, Jewish artistic culture in various periods reflected the culture in which they lived. Compared to music or theater, there is less of a specifically Jewish tradition in the visual arts. The most likely and accepted reason is that, as has been previously shown with Jewish music and literature, before Emancipation Jewish culture was dominated by religious tradition. As most Rabbinical authorities believed that the Second Commandment prohibited much visual art that would qualify as "graven images", Jewish artists were relatively rare until they lived in assimilated European communities beginning in the late 18th century.[32][33] It should be noted however, that despite fears by early religious communities of art being used for idolatrous purposes, Jewish sacred art is recorded in the Tanakh and extends throughout Jewish Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The Tabernacle and the two Temples in Jerusalem form the first known examples of "Jewish art". During the first centuries of the Common Era, Jewish religious art also was created in regions surrounding the Mediterranean such as Syria and Greece, including frescoes on the walls of synagogues, as well as the Jewish catacombs in Rome. Middle Age Rabbinical and Kabbalistic literature also contain textual and graphic art. However, in the ghettos of Europe it was even illegal for Jews to create art. Johnson again summarizes this sudden change from small amount of participation of Jews in visual art (as in many other arts) to a large entry of them into this branch of European cultural life:

Again, the arrival of the Jewish artist was a strange phenomenon. It is true that, over the centuries, there had been many animals (though few humans) in Jewish art: lions on Torah curtains, owls on Judaic coins, animals on the Capernaum capitals, birds on the rim of the fountain-basis in the fifth-century Naro synagogue in Tunis; there were carved animals, too, on timber synagogues in eastern Europe - indeed the Jewish wood-carver was the prototype of the modern Jewish plastic artist. A book of Yiddish folk-ornament, printed at Vitebsk in 1920, was similar to Chagall's own bestiary. But the resistance of pious Jews to portraying the living image was still strong at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Jewish secular art, therefore, just like Jewish participation in European classical music, did not really appear until after Emancipation and escalated during the rise of Modernism in the 20th century. There were many Jewish artists in the 19th century, but Jewish artistic activity boomed during the end of World War I. According to Nadine Nieszawer, "Until 1905, Jews were always plunged into their books but from the first Russian Revolution, they became emancipated, committed themselves in politics and became artists. A real Jewish cultural rebirth".[39] Individual Jews figured in the modern artistic movements of Europe— Art Deco (Tamara de Lempicka[40]), Bauhaus (Mordecai Ardon, László Moholy-Nagy), Constructivism (Boris Aronson, El Lissitzky), Cubism (Nathan Altman, Jacques Lipchitz, Louis Marcoussis, Max Weber, Ossip Zadkine[40]), Expressionism (Erich Kahn, Jack Levine, Jules Pascin,[40] Chaim Soutine), Impressionism (Max Liebermann, Leonid Pasternak, Camille Pissarro[40]), Minimalism (Richard Serra[40]), Orphism (Sonia Delaunay), Realism (Raphael Soyer), Social Realism (Leon Bibel, Ben Shahn, Raphael Soyer), Surrealism (Victor Brauner, Marc Chagall, Méret Oppenheim and Man Ray), the Vienna School of Fantastic Realism (Arik Brauer, Ernst Fuchs[40]) and Vorticism (David Bomberg, Jacob Epstein), as well as some not necessarily affiliated with a single movement (Balthus,[40] Eduard Bendemann, Mark Gertler, Maurycy Gottlieb, Nahum Gutman, Menashe Kadishman, Moise Kisling, R. B. Kitaj, Mane-Katz, Isidor Kaufman, Michel Kikoine, Pinchus Kremegne, Amedeo Modigliani, Elie Nadelman, Felix Nussbaum, Charlotte Salomon, Boris Schatz, George Segal, Anna Ticho, William Rothenstein)— and have been particularly prominent in the post-World War II United States and UK— Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, the pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, and Judy Chicago. During the early 20th century Jews figured particularly prominently in the Montparnasse movement, and after World War II among the abstract expressionists: Helen Frankenthaler, Adolph Gottlieb, Philip Guston, Al Held, Franz Kline, Lee Krasner, Barnett Newman, Milton Resnick and Mark Rothko, as well as the Postmodernists.[41] Many Russian Jews were prominent in the art of scenic design, particularly the aforementioned Chagall and Aronson, as well as the revolutionary Léon Bakst, who like the other two also painted. One Mexican Jewish artist was Pedro Friedeberg; it was once thought the Frida Kahlo's father was Jewish, but historians have determined that he was not. Gustav Klimt was not Jewish, but nearly all of his patrons were. Among major artists Chagall may be the most specifically Jewish in his themes. But as art fades into graphic design, Jewish names and themes become more prominent: Leonard Baskin, Al Hirschfeld, Ben Shahn, Art Spiegelman and Saul Steinberg. And in the golden age of American comic books, the Jewish role was overwhelming: Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, creators of Superman, were Jewish, as were Bob Kane (né Robert Cohen), Martin Goodman, Joe Simon, Jack Kirby, and Stan Lee of Marvel Comics; and William Gaines and Harvey Kurtzman, founders of Mad. |